- Constantine

- (d. 337)Roman emperor (r. 306-337) who, with Diocletian (r. 284-305), restored order to the Roman world and laid the foundation for the empire's success for centuries to come. His achievements were numerous, including the establishment of a new capital at Constantinople and reform of the coinage. He is important also for his military reforms and his introduction of many Germans into the Roman military, beginning a process known as the barbarization of the Roman army. He is particularly important for his conversion to Christianity and for becoming the first Christian emperor of the Roman Empire. Indeed, his activities as a Christian emperor had great consequences for the church and for the Germanic peoples who inherited the empire in the fifth and sixth centuries.Constantine rose to power in the early fourth century in the wake of his father's death and the retirement of the leading Roman emperor, Diocletian, and his colleague Maximian. Diocletian had spent the preceding twenty years creating a delicate system of shared government that was designed to prevent the political and military collapse of the preceding half century. After he retired in 305, with the hope that his succession plan would succeed, he instead witnessed the rapid destruction of that system. It was in the civil wars that followed the retirement of Diocletian that Constantine rose to power.One of the most critical moments in Constantine's struggle for power came in the year 312, when he fought his rival Maxentius, Maximian's son, for control of the Western Empire. The Battle of the Milvian Bridge, one of the bridges across the Tiber River to Rome, was won by Constantine, and it brought him possession of the ancient capital and the Western imperial title. His victory was preceded by a great vision that was the starting point, if not actual cause, of Constantine's conversion to Christianity. According to the church historian Eusebius in his biography of the emperor, Constantine told his biographer that he saw the sign of the cross in the heavens bearing the inscription "In this sign conquer." His victory confirmed the validity of the vision and led him to accept Christianity. And it was indeed in the following year that, with the Eastern emperor Galerius, Constantine issued the Edict of Milan, which legalized Christianity in the empire. He then ruled the empire with a colleague in the east, first Galerius and then Licinius, until 324, when he defeated Licinius in battle and reunited the empire. He founded a new capital, Constantinople (now Istanbul, Turkey) in 330 and ruled as sole emperor, although often with his sons as caesars, until his death in 337.Constantine's reign had significant consequences for the Germanic successor kingdoms that emerged in the wake of the collapse of the Western Empire, as well as for much of early medieval Europe in general. As the first Christian emperor he established an important model for numerous kings and emperors, including the great Frankish rulers Clovis and Charlemagne, as well as for early medieval writers like Gregory of Tours. His relations with the church set an important precedent for later rulers in both the barbarian kingdoms and the Byzantine Empire (as the Eastern Empire came to be called). On two occasions, both interestingly after military victories, one that brought him control over the western half of the empire and the other over the entire empire, Constantine convened church councils to decide major issues of the faith. The second of the councils, at Nicaea in 324, decided one of the fundamental tenets of the Christian faith, the relationship between God the Father and God the Son. Constantine presided over the council and participated in debate, and his presence may have influenced the outcome. At the very least, it set the model for the involvement of the emperor in the affairs of the church and asserted the right and responsibility of the emperor to convene church councils.Constantine's involvement in the Council of Nicaea may also have led to the denunciation of the teachings of Arius and the declaration of Arianism as a heresy. Constantine, however, wavered in his support for orthodoxy and allowed the growth of Arianism in the empire. Consequently the Germanic tribes living along the imperial frontier were evangelized by Arian Christians, and many of the tribes that converted to Christianity accepted the Arian version. Constantine's religious legacy, therefore, was mixed. He provided a positive model of Christian rulership for later kings and emperors, but also contributed to the conversion of many barbarians to Arian Christianity, a process that later caused difficulties for Arian Christian kings, like Theodoric the Great, who ruled over Catholic Christian subjects in the post-Roman world.Constantine's other legacy to the late Roman and early medieval world was his recruitment of Germans into the Roman army. It is one of the paradoxes of Constantine's reign that he was criticized by contemporaries and has been remembered by historians for the so-called barbarization of the army when he strove to identify himself as a conqueror of the barbarians and the "Triumpher over the barbarian races" (Triumfator, Debellator, Gentium barbararum). But, indeed, he both waged war against the Germans and other peoples along the frontier and expanded the existing policy of promoting Germans to high-ranking military posts.His wars against the Germans were intended to stabilize a frontier that had proved particularly porous during the crisis the empire faced in third century and to provide Constantine a glorious military record to parallel his successes in the civil wars. Toward those ends, he waged wars against a number of Germanic peoples along the frontiers. He fought border wars with the Alemanni along the Rhine River in an attempt to preserve the integrity of that frontier, which had been an important point of entry for the Germans in the third century. The emperor also faced the Visigoths along the Danubian border in the late 310s and early 320s. Here again he sought to restore the stability of the old frontier and even extend Roman power to the limits established by the emperor Trajan in the early second century. Constantine responded to Visigothic incursions into Roman territory with a series of battles that allowed the emperor to repel the invaders and extend Roman authority. Constantine's victories forced the Visigoths to surrender. The extent of his expansion beyond the Danube remains uncertain, however, and the Visigoths launched another attack in the mid-320s. Constantine sent his son against them, who successfully defeated them and extracted a treaty that required the Visigoths to defend the empire. Unfortunately for the empire, Constantine's successes were short-lived, and by the end of the fourth century, at the latest, his settlements had broken down, and various Germanic tribes had crossed into the empire.Despite actively fighting the barbarians, Constantine also enrolled many of them in the army. Although this policy was not new, Constantine included larger numbers of Germans than any of his predecessors, which caused serious problems for the empire in the following century. The army itself had increased in size to meet internal and external threats, and in Constantine's time may have numbered as many as 600,000 men, a number that included traditional Roman legionnaires as well as auxiliary soldiers (auxiliae). The auxiliaries were more numerous in Constantine's army than they had traditionally been, in fact more numerous than the legionnaires. It was this contingent that was made up mostly of Germans, so that the army was nearly half immigrant. And the Germans found places at all levels of the Roman army. The highest-ranking officers were Germans, and Constantine's personal bodyguard was made up of Germans. Constantine also reorganized the army, dividing it into a frontier force and a central strike force, and German soldiers were in both units. Constantine's use of Germans thus did contribute to what has been called the barbarization of the army, a process that, in some ways, undermined Rome's ability to defend itself against other Germanic invaders. On the other hand, it allowed the barbarians to identify themselves with the empire and its values and thus become Romanized.

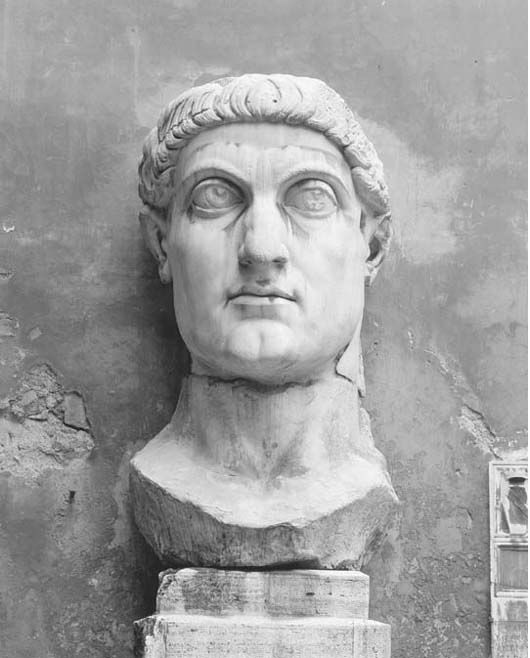

Marble bust of Emperor Constantine (Araldo de Luca/Corbis)See alsoBibliography♦ Barnes, Timothy D. Constantine and Eusebius. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1981.♦ Brown, Peter. The World of Late Antiquity, a.d. 150-750. London: Thames and Hudson, 1971.♦ Burckhardt, Jacob. The Age of Constantine the Great. Trans. Moses Hadas. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1983.♦ Grant, Michael. Constantine the Great: The Man and His Times. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1994.

Marble bust of Emperor Constantine (Araldo de Luca/Corbis)See alsoBibliography♦ Barnes, Timothy D. Constantine and Eusebius. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1981.♦ Brown, Peter. The World of Late Antiquity, a.d. 150-750. London: Thames and Hudson, 1971.♦ Burckhardt, Jacob. The Age of Constantine the Great. Trans. Moses Hadas. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1983.♦ Grant, Michael. Constantine the Great: The Man and His Times. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1994.

Encyclopedia of Barbarian Europe. 2014.